Only the circumstance that Longfellow lived after Irving instead of before him prevented his becoming, in at least one sense, the first American man of letters. Washington Irving, who was the first to win a transatlantic reputation, was essentially a man of letters; Nathaniel Hawthorne had much of the poet in his intellectual character, though he wrote only in prose; Longfellow was distinctly a poet, a fact that is plainly discernible in “Hyperion” and “Outre-Mer,” as well as in “ Evangeline” and “Hiawatha.”

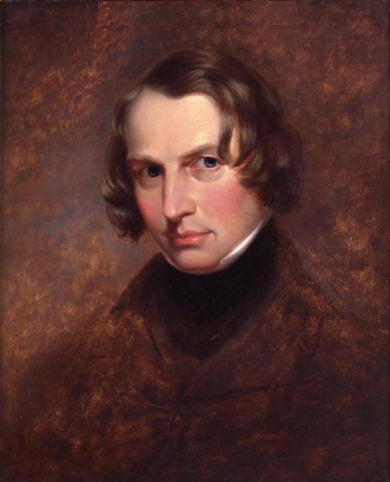

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Professor of Modern Languages, Harvard College, 1840.

He sat for this portrait when he was 33.

In him the reputation established by Irving and sustained by Hawthorne suffered no dimming. There is no one American author whose genius towers conspicuously above all others, but Longfellow, by the nobility of his thought and the perfection of his form, whether he wrote in verse or in prose, easily holds a place among the greatest.

One of his characteristics is poetic maturity. Any collection of his best poems would include something that was written in his teens and something that was written after he was seventy years old. There was certainly growth in his boyhood and youth, but there were no evidences of decay in his old age. His early work was mature but not precocious, and his later work is simple but not childish.

Like most people, especially those of talent or genius, his work and his interest in it were not absolutely even, but were subject to a tidal ebb and flow. Thu s we find him at the age of twenty-two writing from Germany, “My poetic career is finished.” He was mistaken. He was born a poet and such he remained to his last year. Again when he was about forty-five years of age, he feared he would write no more poetry. But he was soon at work with new subjects, treating them with undiminished grace. To his native talent he added habits of industry, regularity of life and of work, patience in revision: and the result is a large collection of poems every line of which reflects credit on the author.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born at Portland, Maine, Feb. 27, 1807. He was a descendant of William Longfellow of Hampshire, England, who emigrated to this country and settled in Newbury, Mass., in 1676. On his mother’s side he was a lineal descendant of John Alden and Priscilla, of Mayflower fame, and whom he charmingly celebrated in his poem, “The Courtship of Miles Standish.” His father, a lawyer, was a graduate of Harvard and an intimate friend of Channing, and his mother was a daughter of Gen. Peleg Wadsworth.

Thus Henry was not only entitled to an “aristocracy of brains,’’ but his childhood was passed amid influences of the finest intellectual and social culture. His first lines, written at the age of thirteen, he had the pleasure of seeing in print in a local paper, and the anguish of hearing it severely criticized. During his college life he published some poems, and it is in keeping with his character that his first receipts were invested in the complete works of Chatterton.

At the age of fourteen he entered Bowdoin College, from which he was graduated in 1825. Hawthorne was a classmate, and though the two were not intimate in college, yet they became fast friends afterwards, when both had successfully entered the field of literature. The basis of their friendship seems to have been the mutual and generous appreciation of the literary triumphs of each, and this friendship continued until the death of Hawthorne in 1864, and was placed in permanent remembrance by Longfellow’s beautiful poem, “Hawthorne.”

This friendship is deserving of mention, not merely because of the striking talent of the two men, but specifically because the theme of “Evangeline” was first given to Hawthorne and he generously passed it over to his friend, believing that the latter would be able to give it a more perfect treatment.

After graduation he began the study of law, not because he was satisfied with that, but because it was the least unsatisfactory within his reach at that time. Soon the trustees of Bowdoin made him an informal offer of the Professorship of Modern Languages. He at once went to Europe to fit himself for these duties. More than three years he devoted to close study in France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Holland, and England. After a term of successful, not to say eminent, service in this alma mater he was, in 1835, elected Professor of Belles-Lettres in Harvard College.

This was the occasion of a second trip to Europe, when he spent his time mostly in Denmark and Sweden, Holland and Germany, Switzerland and the Tyrol. It was at this time that his wife, whom he had married four years previously, died in Rotterdam. Her memory he later enshrined in “Footsteps of Angels”

The Being Beauteous,

Who unto my youth was given,

More than all things else to love me;

And is now a saint in heaven.”

In 1837 Longfellow took up his residence in Cambridge, living, first as lodger and afterwards as owner, in the historic “Craigie House,’’ celebrated as the residence of George Washington and later as that of various eminent and scholarly men. In this house he passed nearly a half-century, and for more than a generation it has been inseparably associated with his name. In 1842 he married Miss Frances Appleton, whose, father purchased for him the house and the neighboring grounds.

After nine years of married life she died a tragic death. Her light summer clothing accidentally caught fire and she was burned, dying from the burns and the shock. Eighteen years later he wrote “The Cross of Snow,” but showed the lines to no one; they were found in his portfolio after his death:

Such is the cross I wear upon my breast

These eighteen years, through all the changing scenes

And seasons, changeless since the day she died.

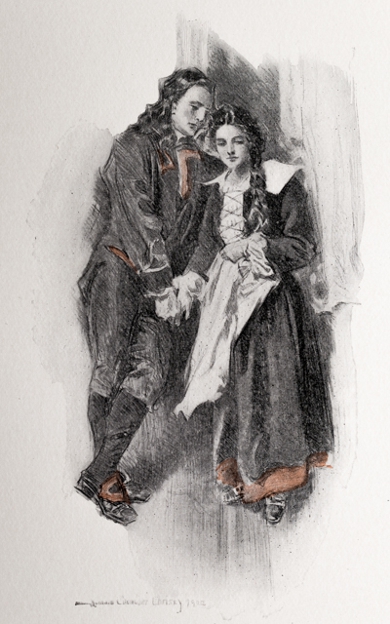

“Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie”

Poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

This leads to the remark that not a few of his poems are in a sense autobiographical, at least they grew directly out of his own experience. Among this number may be mentioned : “To the River Charles,” “The Children’s Hour,” “Resignation,” “The Open Window.” This list might be lengthened indefinitely. The exquisite poem, “The Two Angels,” was written upon the birth of his daughter and the death of the wife of James Russell Lowell.

In 1854, after holding his professorship in Harvard for nearly twenty years, he resigned to give his entire time to literary production. The duties of his professorship were not light, and to these he had added the labors of authorship, so that for some years his labors were irksome and he surely earned the luxury of literary leisure. The succeeding years, however, show that he was not idle, for much of his work and some of his best work, including “Hiawatha,” “Evangeline,” and “Tales of a Wayside Inn,” were the fruit of his “leisure.”

Though he was never a man of wealth, he was at all times possessed of a competency, so that he never suffered from poverty nor was he driven to uncongenial work. His success was continuous, so that he was always able to gratify his taste for art, music, the drama, travel, and chiefly for “the divine art of hospitality,” which he so generously and gracefully dispensed. From the middle of his life to its close his Craigie House was the Mecca of a continually increasing stream of pilgrims, including all sorts and conditions of men, from the learned to the mere sight-seer, coming from both continents, to do him honor. Thus he spent his last years in receiving homage and dispensing truth, beauty, and goodness until his death, March 24, 1882.

One element of his poetry which is evident to even the most cursory reader is the tone of deep religious emotion which pervades it all. So early as his inaugural at Bowdoin he said: “It is this religious feeling, this changing of the finite for the infinite, this constant grasping after the invisible things of another and a higher world, which makes the spirit of modern literature.”

Towards this ideal he steadily worked through a long and active life. To those poems which merely breathe the spirit of Christian piety may be added a large number which are religious in form. A volume of considerable size could be culled under some such title as “Poems of Sorrow and Comfort.” Special mention may be made of those which touch the subject of death, including “The Reaper and the Flowers,” “Two Angels,” “Resignation,” “Auf Wiedersehen,” and a host of others not less devout.

The reader observes also the absence of the wit and humor which is almost universal in poets. While Longfellow was always cheerful, he was never droll.

It is to be noted that his lyrics are genuine lyrics—that is to say, they can be sung. Many of them have been set to music and have been cordially received both in parlors and in concerts. Among these may be mentioned “ The Day is Done,” “The Arrow and the Song,” “ Daybreak,” “The Bridge,” “ Good-night, Beloved,’’ and “Stars of a Summer Night.”

To the present writer it seems as if Longfellow will hold a permanent place in literature. Hawthorne, who was surely a good judge, wrote: “I read your poems over and over, and over again, and continue to read them at all my leisure hours; and they grow upon me at every re-perusal.”

The perspicacity of his style is by some considered a fault and by others a virtue. His meaning is expressed with absolute clearness. There is no more doubt as to what he intended to say than there is of the Ten Commandments or the Beatitudes. His meaning is so plain that the reader misses the intellectual gymnastics required to discover the poet’s thought. He does all the work, leaving none for the reader. If this be a fault, it is shared by Wordsworth, Byron, and Burns.

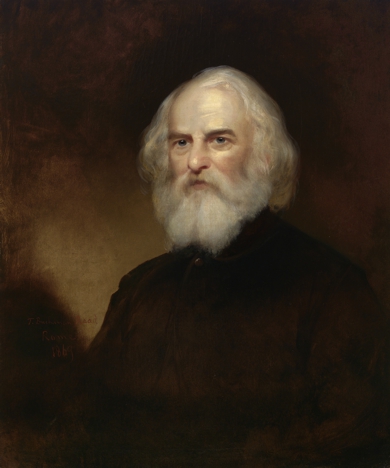

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, American Poet, 1869; 62 years old.

It is not easy to classify Longfellow’s poetry, including, as it does, so wide a range of subject and of treatment. There are dramas, lyrics, narratives, and, not least, translations. His subjects are drawn from France, Spain, Scandinavia, Italy, and the Great West. All these widely different subjects are, with astonishing equality, treated delicately, beautifully, and with refinement. He exhibits “a soul clothed with human affections and divine aspirations.” He was a good, pure, true man, and he gave the best that was in him.

Where all is wrought out with so much care, it is not easy to name his best poem, or to give a list of what may be called his best poems, for there are dozens of them any one of which would cause his name long to be held in loving remembrance, had he written no other. But the one which will always be very closely linked to his fame is “Evangeline.”

The outline of this poem is the separation of two lovers and the long search of the heroine for her betrothed. The lovers have grown up from childhood in their simple, unaffected, affectionate life in Acadia until the deportation by the British, when they are separated. Evangeline starts on a pilgrimage of search for Gabriel which takes her through the South and the West. At last in old age, she finds him dying in a hospital in Philadelphia and ministers to him in his last hours. The heartbreaking story is narrated with profound sympathy, and the descriptions of natural scenery which are frequently introduced are beautiful in the last degree. The poem cannot be criticized, it can only be admired. Emerson confessed to a tear on reading it.

Dr. S. G. Howe wrote to the author: “You feed five times five thousand souls with spiritual food which makes them forever better and stronger .... I can [but] admire the instructive story, the sublime moral, the true poetry, which it contains. Patience, forbearance, long-suffering, love, faith,-these are the things which ‘Evangeline’ teaches.” Hawthorne wrote: “I have read ‘Evangeline’ with more pleasure than it would be decorous to express.”

The verse chosen is hexameter. At that time it was a dictum of critics that that measure, while perfect for Greek and Latin, was unsuitable for the English language. Longfellow chose the form deliberately and never doubted the wisdom of it. With very few exceptions the critics agreed with him—in this particular case. Lowell’s judgment, both of the verse and the thought, will doubtless be final:

’Tis truth that I speak,

Had Theocritus written in English, not Greek,

I believe that his exquisite sense would scarce change a line

In that rare, tender, virgin-like pastoral, Evangeline.

That’s not ancient nor modern, its place is apart

Where time has no sway, in the realm of pure Art.

’Tis a shrine of retreat from Earth’s hubbub and strife,

As quiet and chaste as the author’s own life.

Pressing close to “Evangeline” in popularity, at least, is the “Song of Hiawatha.” This embodies certain Native American legends. It is not a copy of Indigenous life; it is an idealization of the best of that life which is so rapidly disappearing. From a note by the author we learn that the foundation of this epic is the tradition of Hiawatha, a person of miraculous birth, who was sent among them to clear their rivers, forests, and fishing grounds, and to teach them the arts of peace.

Into this tradition the author wove other curious legends. The scene of the poem is on the southern shore of Lake Superior, in the region between the Pictured Rocks and the Grand Sable. The narrative is fascinating, and the fidelity with which it portrays the mythology and customs of the people with whom it deals is fully attested Schoolcraft, who is the standard authority on the subject.

The “Tales of a Wayside Inn” is a series of narrative poems supposed to be told by a company of men who met at the old Sudbury Inn, the tales being introduced by a prelude and connected by interludes.

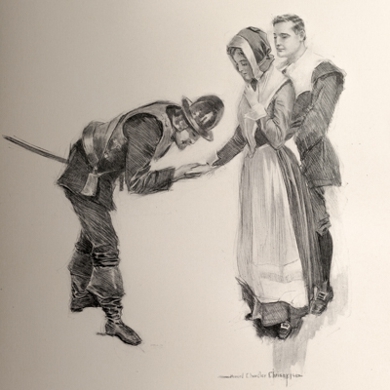

“The Courtship of Miles Standish “ is a picture of Puritan days, not less fascinating than the cadences of “Hiawatha.” The story of the love of John Alden and the beautiful Priscilla is told with every grace of poetry, but not sacrificing fidelity to truth.

“The Building of the Ship,” modeled after Schiller’s “Lay of the Bell,” is charming in its conception and perfect in its details. It leads up to the climax, which is a clarion ring of patriotism:

Thou, too, sail on, O Ship of State,

Sail on, O UNION, strong and great!

“The Courtship of Miles Standish”

Poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The dramas, including “The Spanish Student,” “Michael Angelo,” and a trilogy, “Christus,” fill the greatest bulk of any one class of Longfellow’s poems, but they are not his greatest works in any other sense. They are dramatic in form and in name, but not in fact, because, while they are good poetry, they are lacking in the action which is essential to drama .

His translations are noteworthy. Not to mention the large number of brief poems, his translation of Dante’s “Divine Comedy” is a monumental work, quite enough in itself to establish the reputation of one scholar and poet.

During the closing years of his life, after nearly all of his intimate friends had died, he felt the loneliness of his situation—despite the unparalleled and affectionate honors which he continually received—and this fact is made apparent in his verse. At the fiftieth anniversary of his graduation he returned to Bowdoin College as poet.

His subject, Mlorituri Salutamus, was taken from the words of the gladiator who, upon entering the arena, made his obeisance to the emperor in the words, “O Cæsar, we who are about to die salute thee.” In a different spirit, but in the same words, the poet, nearly seventy years of age, saluted the college, the scenes of his youth, the instructors, the younger generation of scholars.

The last collection of his poems bore the significant title of “Ultima Thule,” suggesting the last resting place of land before the ocean of eternity. However, it was in him to work and he could not rest in idleness. His very last verses were still more prophetic. These were “The Bells of San Blas,” and ended with the following lines:

Out of the shadow of night

The world moves into light;

It is daybreak everywhere!

Longfellow was a noble type of the cultivated scholar, the polished gentleman, the sterling patriot, and the generous host. As was fitting, the honors which came to him through a long life accumulated during his last years. His books found a place not only in the libraries of scholars, but equally in the homes of the common people.

For many years there was a stream of pilgrims to Craigie House, including both famous and plain people, not only Americans but also Europeans. Among the latter his biographer mentions the following names: Hughes, Froude, Trollope, Wilkie Collins, William Black, Kingsley, Professor Bonamy Price, Dr. Plumptre, Dean Stanley, Lord Houghton, Lord and Lady Dufferin, the Duke of Argyll, CoquereI, Salvini, Christine Nilsson, and Madame Titjens. To these may be added Dom Pedro, emperor of Brazil. When he was last in England he was honored by Queen Victoria, the Prince of Wales, and Gladstone—which meant the entire English people. He was decorated by both the great universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

But an honor which was certainly not less than that of royalty and the universities was found in the devotion of the school children of the neighborhood: When “the spreading chestnut-tree,” under which the village smithy stood, was cut down, seven hundred children contributed their dimes to have a library chair made from this for the poet. The chair was placed in his library on his seventy-second birthday.

After this large numbers of public schools, not only in New England but equally in distant parts of the land, began the practice of celebrating his birthday by reciting selections from his poems, and by biographical essays. The zest with which the children carried out these plans everywhere attested the sincerity of their homage.

The highest honor England confers on her illustrious dead is a memorial in Westminster Abbey. This honor had been extended across the sea to Longfellow, to whom a memorial bust was placed in the famous Poets’ Corner.

His life was passed without a stain, and his verse is without a flaw. “He wrote no line which dying he would wish to blot, or which living he might not justly be proud of.”

—HENRY KETCHAM.