The materials for The Song of Hiawatha are found in the myths and legends of certain Native American Nations, which have been collected by Henry R. Schoolcraft and published in 1839 under the title of Algic Researches. This book—two small Volumes in one—is out of print. As it is not accessible to the general reader, such portions of it as throw light upon Longfellow’s poem are given below, partly verbatim and partly in brief condensations.

From the first Hiawatha was very popular. For the first year or two after its publication, its sale was considerably greater than that of any other volume by the author, and was for those days enormous. This popularity was not confined to the general reading public, but extended to literary people and specialists in folklore. The poem, apart from its interest as a poem, will always be valuable for the reason that it crystallizes—in a form remarkably fascinating—these rituals, myths and legends of a people that have almost passed away.

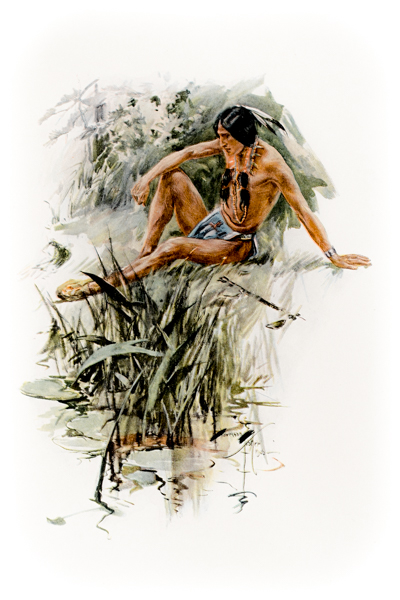

The Rite of Fasting. The rite of fasting is one of the most deep-seated and universal of Native American rituals. It is practiced among all the North American First Nations, and is deemed by them essential to their success in life in every situation. No young man is fitted and prepared to begin the career of life until he has accomplished his great fast. Seven days appear to have been the ancient maximum limit of endurance, and the success of the devotee is inferred from the length of continued abstinence to which he is known to have attained.

By the river’s brink he wandered

These fasts are anticipated by youth as one of the most important events of life. They are awaited with interest, prepared for with solemnity, and endured with a self-devotion bordering on the heroic. Character is thought to be fixed from this period, and the primary fast, thus prepared for and successfully established, seems to hold that relative importance to subsequent years that is attached to a public profession of religious faith in civilized communities. It is at this period that the young men and the young women “see visions and dream dreams,” and fortune or misfortune is predicted from the guardian spirit chosen during this religious ordeal. The hallucinations are divine inspiration.

The effect is deeply felt and strongly impressed on the mind; too deeply, indeed, to be ever obliterated in after life. The father, in the circle of his lodge, the hunter in the pursuit of the chase, the warrior in the field of battle, think of the guardian genius which they fancy to accompany them, and trust to his power and benign influence under every circumstance. This genius is the absorbing theme of their silent meditations, however deeply mused upon, the name is never uttered, and every circumstance connected with its selection, and the devotion paid to it, is most studiously and confessedly concealed even from their nearest friends.

Fasts in subsequent life appear to have for their object a renewal of the powers and virtues which they attribute to the rite. And they are observed more frequently by those who strive to preserve unaltered the ancient state of society among them, or by men who assume austere habits for the purpose of acquiring influence in their nation, or as preparatives for war or some extraordinary feat.

It is not known that there is any fixed day observed as a general fast. So far as a rule is followed, a general fast seems to have been observed in the spring, and to have preceded the general and customary feasts at that season.

It will be inferred from these facts, that Native Americans believe fasts to be very meritorious. They are deemed most acceptable to the manitoes or spirits whose influence and protection they wish to engage or preserve. And it is thus clearly deducible that a very large proportion of the time devoted to this secret worship, so to say, is devoted to the guardian or intermediate spirits, and not to the Great Spirit or Creator.

The Four Winds. Ten brothers conquered the Mammoth Bear, and obtained the Sacred Belt of Wampum, the great object of previous warlike enterprise, and the great means of happiness to men. The chief honor of this achievement was awarded to Mudjekewis, the youngest of the ten, who received the government of the West Winds. He is therefore called Kabeyun, or “father of the winds.” To his son, Wabun, he gave the East; to his son Shawondasee, the South; and to his son Kabibonokka, the North. Nanabozho, being an illegitimate son, was left unprovided.

It should be noted that Longfellow based his character Hiawatha on the Ojibwe moral, heroic, and trickster figure Nanabozho. —Ed.

When he grew up, and obtained the secret of his birth, Nanabozho went to war against his father , and having brought the latter to terms, he received the government of the Northwest Winds, ruling jointly with his brother Kabibonokka the tempests from that quarter of the heavens.

Shawondasee is represented as an affluent, plethoric old man, who has grown unwieldy from overeating and seldom moves. He keeps his eyes steadfastly fixed on the north. When he sighs in autumn, we have those balmy southern airs, which communicate warmth and delight over the northern hemisphere, and make the Indian Summer.

He beheld her yellow tresses

Changed and covered o’er with whiteness,

Covered as with whitest snow-flakes.

One day, while gazing toward the north, Shawondasee beheld a beautiful young woman of slender and majestic form standing on the plains. She appeared in the same place for several days, but what most attracted his admiration, was her bright and flowing locks of yellow hair. Ever dilatory, however, he contented himself with gazing. At length he saw, or fancied he saw, her head enveloped in a pure white mass like snow. This excited his jealousy toward his brother Kabibonokka, and he threw out a succession of short and rapid sighs-when lo! The air was filled with light filaments of a silvery hue, but the object of his affections had forever vanished. In reality, the southern airs had blown off the fine-winged seed-vessels of the prairie dandelion, Nothocalais cuspidate.

“My son,” said the narrator, “it is not wise to differ in our tastes from other people; nor ought we to put off, through slothfulness, what is best done at once. Had Shawondasee conformed to the tastes of his countrymen he would not have been an admirer of yellow hair; and if he had evinced a proper activity in his youth, his mind would not have run flower-gathering in old age.”

Nanabozho and Mudjekeewis. Nanabozho was brought up by his grandmother, Nokomis. When he reached the period of youth and felt his growing strength, he fell to thinking of his parents, of whom he had never heard. After some insistence be learned that his father was the West Wind, whose cruelty had caused the death of his mother at his birth, and that she, Nokomis, had taken charge of him from infancy. The North, East, and South Winds were his brothers.

At the aspect of his father.

On the air about him wildly

Tossed and streamed his cloudy tresses,

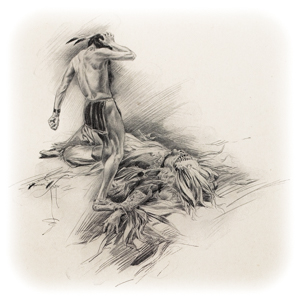

He instantly determined to take vengeance upon his father and started west in search of him. Upon meeting, the two cultivated each other’s acquaintance with an outward show of friendliness. Nanabozho then asked his father if there was anything he feared. The latter at first disclaimed all fear, but, after skillful coaxing, confessed to a fear of a certain black stone, found in such and such a place, the only thing on earth that had power to injure him.

The father then asked a like question of the son, who simulated abject terror of the bulrush-root. The son then set out to procure the black stone, and the father secretly set out to procure the root of the bulrush. Upon their next meeting, the son accused the father of causing the mother’s death, and the fight was on. The son was strong and possessed the fateful black stone. The father, though his weapon was the harmless bulrush, made a desperate though losing fight, and was crowded back over rivers, lakes, and mountains, until he came to “the brink of the world.” There hostilities were suspended and the father proposed a settlement.

He set forth the fact that it was impossible to kill him, and that the four quarters of the earth were already occupied, but made the following proposition: “You can do a great deal of good to the people of this earth, which is infested with large serpents, beasts, and monsters [cannibals], who make great havoc among the inhabitants. Go and do good. You have the power now to do so, and your fame with the beings of this earth will last forever.”

This pacified Nanabozho who returned to his lodge, where his grandmother nursed him to the recovery of his wounds.

Down into the depths beneath him,

“Take my bait, O Sturgeon, Nahma!

Come up from below the water,

Let us see which is the stronger!”

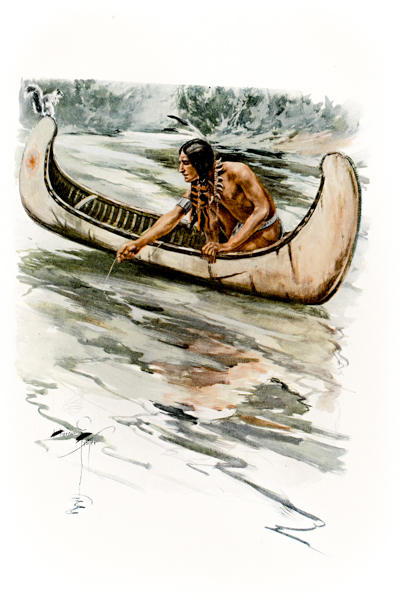

Nanabozho’s Fishing. Nokomis then told him that her husband had been killed by Pearl Feather, since which time she had bad no oil for her hair, which was now falling out for the lack of it. He asked her to make a line of cedar-bark while he made a canoe. When all was ready, he went out into the middle of the lake to fish for the king of fishes, the sturgeon. Casting his line, he shouted a challenge.

The trout took the hook, and pulled hard, but when Manabozbo saw that it was only the trout he shamed it off. Then the sun-fish took the hook, with a similar result. The fisherman was loud in his challenging until the sturgeon swallowed fisherman and canoe, at one gulp. The fisherman being now in the belly of the fish, seized his war-club and pounded away at the heart of the fish, who became sick and showed a disposition to vomit up his unusual meal. Nanabozho prevented this by placing his canoe across the opening of the throat and so blocking the passage.

By the vigorous use of his war-club he killed the fish, and then rested in his not uncomfortable ark to await developments. The fish was washed upon the shore, where the gulls attacked it and ate their way through, thus releasing him. He returned to his lodge, which was near at hand, and invited his grandmother to help herself to all the oil she wanted.

Nanabozho and the Pearl-Feather. His next adventure was an attack upon Pearl Feather to avenge the death of his grandfather. This Manito lived on the opposite side of the great lake, and his abode was guarded, first, by two fiery serpents, and secondly, by a large mass of gummy matter floating upon the water and of a nature so sticky that nothing could pass. Nanabozho got by the serpents by a trick, getting them to turn their heads. He then shot them dead with arrows. He then oiled the boat and so got over the pitchy substance.

Then came the conflict with Pearl Feather which lasted all day. Nanabozho had but three arrows left. At this point a woodpecker came to his aid with the information that his antagonist had one vulnerable spot, namely, at the lock of hair on the crown of his head. Following the suggestion the warrior aimed as indicated.

Sang the Mama, the woodpecker:

“Aim your arrows, Hiawatha,

At the head of Megissogwon,

Strike the tuft of hair upon it,

At their roots the long black tresses;

There alone can he be wounded!”

Nanabozho. The accounts which Native Americans hand down of a remarkable personage of miraculous birth, who waged a warfare with monsters, performed the most extravagant and heroic feats, underwent a catastrophe like Jonah’s, and survived a general deluge, constitute a very prominent portion of their cabin lore. Interwoven with these leading traits are innumerable tales of personal achievement, sagacity, endurance, miracle, and trick, which place him in almost every scene of deep interest that could be imagined, from the competitor on the playing field, to a giant-killer, or a mysterious being of stern, all-knowing, superhuman power. Whatever man could do he could do. He affected all the powers of a necromancer. He wielded the arts of a demon, and had the ubiquity of a god.

His birth and parentage are obscure. Story says his grandmother was the daughter of the moon. Having been married but a short time, her rival attracted her to a grapevine swing on the banks of a lake, and by one bold exertion pitched her into its center, from which she fell through to the earth. Having a daughter, the fruit of her lunar marriage, she was very careful in instructing her, from early infancy, to beware of the West Wind.

This precaution was neglected, and the West Wind—Mudjekeewis—became the father of Nanabozho, annihilating her at the moment of the birth of her son.

Saying oft, and oft repeating,

“Oh, beware of Mudjekeewis,

Of the West-Wind, Mudjekeewis;

Listen not to what he tells you;

Lie not down upon the meadow,

Stoop not down among the lilies,

Lest the West-Wind come and harm you!”

Very little is told of his early boyhood. He soon evinced the sagacity, cunning, perseverance, and heroic courage which constitute his admiration by Native Americans, and he relied largely upon these in the gratification of an ambitious, vainglorious, and mischief-loving disposition. In wisdom and energy, he was superior to any one who had ever lived before. Yet he was simple when circumstances required it, and was ever the object of tricks and ridicule in others. He could transform himself into any animal he pleased, being man or spirit, as circumstances rendered necessary. He often conversed with animals, fowls, reptiles, and fishes. He deemed himself related to them, and invariably addressed them by the term “my brother,” and one of his greatest resources, when hard pressed, was to change himself into their shapes.

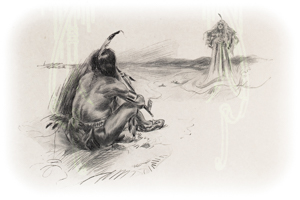

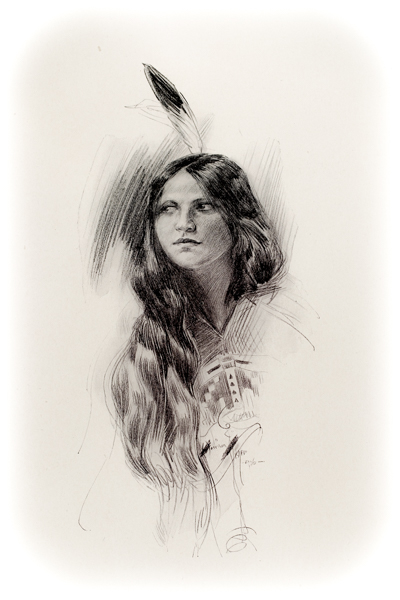

The origin of Indian Corn, an Odjibwe Tale. Wunzh was the name of the youth who was just reaching the period of maturity. Like his father, he was, though poor, contented and grateful to the Great Spirit for such blessings as he had. When he withdrew into solitude for his seven-days fast, he spent the daytime in walking through the woods and over the mountains, which not only gave him the exercise that would make his sleep refreshing, but his observations of plants and flowers prepared his mind for pleasant dreams. He meditated much upon the problem of poverty, and wondered if the Great Spirit would not provide some way whereby living could be obtained easier than hunting and fishing alone. He determined to try to discover this in his visions.

He was duly rewarded. While lying on his bed, faint from fasting, there came a vision of a handsome young man, descending from the sky, richly dressed in clothing of green and yellow, with waving plumes upon his head. The stranger declared the Great Spirit, pleased with his motives of kindness, had sent him to show how be might accomplish his desire and do much good to his kindred. For this purpose, he must rise from his bed and wrestle with him.

Though weak in body he was strong in mind and tried with a good courage. When at the point of exhaustion his beautiful antagonist said, “It is enough for now. I will come again.”

The celestial visitor returned at the same hour the two succeeding days, and the wrestling was repeated with increasing intensity. It was at the point of the hero’s exhaustion on the third clay when the beautiful stranger ceased and declared himself conquered.

On the following day, which was the seventh day of his fasting, Wunzh was to receive food to renew his strength and then to wrestle with the stranger for the last time.

Made the grave as he commanded,

Stripped the garments from Mondamin,

Stripped his tattered plumage from him,

Laid him in the earth, and made it

Soft and loose and light above him;

“As soon as you have prevailed against me,” said he, “you will strip off my garments and throw me down, clean the earth of roots and weeds, make it soft, and bury me in the spot. When you have done this, leave my body in the earth, and do not disturb it, but come occasionally to visit the place, to see whether I have come to life, and be careful never to let the grass or weeds grow over my grave.” He then disappeared.

The next day he returned and his instructions were faithfully carried out by Wunzh. Returning to his father’s lodge, he never forgot his friend’s grave, but visited it throughout the spring, weeding out the grass, and keeping the ground in a soft and pliant state.

Soon the tops of the green plumes were seen coming through the ground and grew rapidly. Days and weeks passed until near the close of the summer. One day, after a long absence in hunting, Wunzh took his father to the scene of his lonesome fast. The lodge had been removed, and the weeds kept from growing on the circle where it had stood; but in its place stood a tall and graceful plant, with bright-colored silken hair, surmounted with nodding plumes and stately leaves, and golden clusters on each side.

“It is my friend,” shouted the lad, “it is the friend of all mankind. It is Mon-Daw-Min. We need no longer rely on hunting alone; for, as long as this gift is cherished and taken care of, the ground itself will give us a living .... Henceforth the people will not alone depend upon the chase or upon the waters.”

So corn came into the world and has ever since been preserved.

In his crown alone was seated;

In his crown too was his weakness;

There alone could he be wounded,

Nowhere else could weapon pierce him,

Nowhere else could weapon harm him.

Kwasind. He was a listless idle boy. He would not play when the older boys played, and his parents could never get him to do any kind of labor. He was always making excuses. His parents took notice, however, that he had fasted for days, but they could not learn what spirit he supplicated or had chosen as the guardian spirit to attend him through life. He was so inattentive to his parents’ requests, that he, at last, became a subject of reproach.

One day, his mother, having bitterly reproached him for his idleness, ordered him to wring out the wet fishnet. He took up the net, carefully folded it, doubled it again and again, making it into a roll, and then wrung it most carefully as if it had been constructed of the most fragile material.

His parents then saw that the reason of his apparent idleness was the possession of supernatural strength.

After this he used his great strength in various ways. Coming upon one of those large, heavy, black pieces of rock which Nanabozho is said to have thrown at his father, he took it up with ease and tossed it into the river. When he was travelling with his father and they came to a narrow pass where the wind had blown a great many trees, thus blocking the way, he lifted the largest pine trees and pulled them out of the way.

He performed so many feats of skill that he excited the envy of the fairies who conspired against his life. They slew him by attacking him upon the crown of the head, the only vulnerable spot in his body, with the burr of the white pine, the only weapon which could be successfully employed for the purpose.

Never heard he an adventure

But himself had met a greater;

Never any deed of daring

But himself had done a bolder;

Never any marvellous story

But himself could tell a stranger.

Iagoo. This personage in the mythology of the Chippewas was unique in the fertility of his powers of exaggeration. He scarcely required more than a drop of water to construct an ocean, or a grain of sand to construct an earth. And he had so happy an exemption from both the restraints of judgment and moral accountability, that he never found the slightest difficulty in accommodating his alleged facts to the most enlarged credulity.” Accordingly, when a fisherman tells his fish story or a hunter or warrior embellishes the account of his exploits, he encounters the comment, “so here we have Iagoo come again.

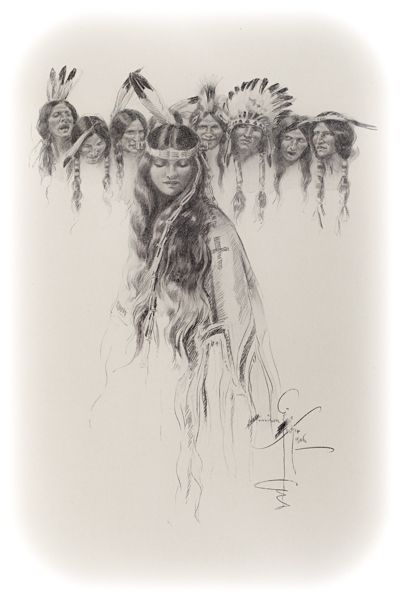

The Son of the Evening Star, an Algonquin Tale. There once lived a northerner who had ten daughters, all of whom grew up to womanhood. They were noted for their beauty, but especially Oweenee, the youngest, who was very independent in her way of thinking. She was a great admirer of romantic places, and paid very little attention to the numerous young men who came to her father’s lodge for the purpose of seeing her. Her elder sisters were all solicited in marriage from her parents, and, one after another, went off to dwell in the lodges of their husbands, or mothers-in-law, but she would listen to no proposals of the kind.

At last she married an old man called Osseo, who was scarcely able to walk, and was too poor to have things like others. They jeered and laughed at her on all sides, but she seemed to be quite happy, and said to them, “It is my choice, and in the end you will see who has acted wisest.” Soon after, the sisters and their husbands and their parents were all invited to a feast, and as they walked along the path, they could not help pitying their young and handsome sister who had such an unsuitable mate.

Handsome men with belts of wampum,

Handsome men with paint and feathers.

Pointed at her in derision,

Followed her with jest and laughter.

But she said: ‘I care not for you,

Care not for your belts of wampum,

Care not for your paint and feathers,

Care not for your jests and laughter;

I am happy with Osseo!’

Osseo often stopped and gazed upwards, but they could perceive nothing in the direction he looked, unless it was the faint glimmering of the evening star. They Leard him muttering to himself as they went along, and one of the elder sisters caught the words, “Pity me, my father.” “Poor old man,” said she, “he is talking to his father. What a pity it is that he would not fall and break his neck, that our sister might have a handsome young husband.”

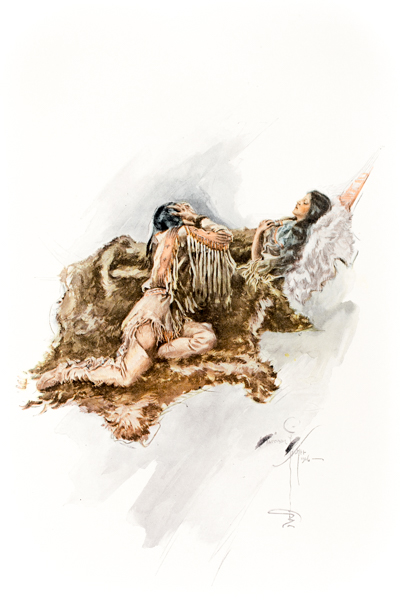

Presently they passed a large hollow log, lying with one end toward the path. The moment Osseo, who was of the turtle totem, came to it, he stopped short, uttered a loud and peculiar yell, and then dashing into one end of the log, he came out at the other, a most beautiful young man, and springing back to the road, he led off the party with steps as light as the reindeer.

But on turning back to look for his wife, behold, she had been changed into an old, decrepit woman, who was bent almost double, and walked with a cane. The husband, however, treated her very kindly, as she had done him during the time of his enchantment, and constantly addressed her by the term of “my sweetheart.”

When they came to the hunter’s lodge, with whom they were to feast, they found the feast ready prepared, and as soon as their entertainer had finished his harangue (in which he told them his feasting was in honor of the Evening or Woman’s Star) they began to partake of the portion dealt out, according to age and character, to each one.

The food was very delicious, and they were all happy but Osseo, who looked at his wife, and then gazed upward, as if he were looking into the substance of the sky. Sounds were soon heard, as if from far-off voices in the air, and they became plainer and plainer, till he could clearly distinguish some of the words.

“My son—my son,” said the voice, “I have seen your affliction and pity your wants. I come to call you away from a scene that is stained with blood and tears. The earth is full of sorrows. Giants and sorcerers, the enemies of mankind, walk abroad in it, and are scattered throughout its length. Every night they are lifting their voices to the Power of Evil, and every day they make themselves busy in casting evil in the hunter’s path.

“You have long been their victim, but shall be their victim no more. The spell you were under is broken. Your evil necromancer is overcome. I have cast him down by my superior strength, and it is this strength I now exert for your happiness. Ascend, my son-ascend into the skies, and partake of the feast I have prepared for you in the stars, and bring with you those you love.

“The food set before you is enchanted and blessed. Fear not to partake of it. It is endowed with magic power to give immortality to mortals, and to change men to spirits. Your bowls and kettles shall be no longer of wood and earth. The one shall become silver and the other wampum. They shall shine like fire and glisten like the most beautiful scarlet.

“Every female shall also change her state and looks, and no longer be doomed to laborious tasks. She shall put on the beauty of the starlight, and become a shining bird of the air, clothed with shining feathers. She shall dance and not work—she shall sing and not cry.

“My beams,” continued the voice, “shine faintly on your lodge, but they have a power to transform it into lightness of the skies, and decorate it with the colors of the clouds. Come, Osseo my son, and dwell no longer on the earth. Think strongly on my words, and look steadfastly at my beams. My power is now at its height. Doubt not, delay not. It is the voice of the Spirit of the Stars that calls you away to happiness and celestial rest.”

The words were intelligible to Osseo, but his companions thought them some far-off sounds of music, or birds singing in the woods. Very soon the lodge began to shake and tremble, and they felt it rising into the air. It was too late to run out, for they were already as high as the tops of the trees.

Osseo looked around him as the lodge passed through the topmost boughs, and behold! their wooden dishes were changed into shells of a scarlet color, the poles of the lodge to glittering wires of silver, and the bark that covered them into the gorgeous wings of insects. A moment more, and his brothers and sisters, and their parents and friends, were transformed into birds of various plumage. Some were jays, some partridges and pigeons, and others gay singing birds, who hopped about displaying their glittering feathers and singing their songs.

But Oweenee still kept her earthly garb, and exhibited all the indications of extreme age. He again cast his eyes in the direction of the clouds, and uttered that peculiar yell which had given him the victory at the hollow log. In a moment the youth and beauty of his wife returned; her dingy garments assumed the shining appearance of green silk, and her cane was changed into a silver feather. The lodge again shook and trembled, for they were now passing through the uppermost clouds, and they immediately after found themselves in the Evening Star, the residence of Osseo’s father.

And her soiled and tattered garments

Were transformed to robes of ermine,

And her staff became a feather,

Yes, a shining silver feather!

“My son,” said the old man, “hang that cage of birds, which you have brought along in your hand at the door, and I will inform you why you and your wife have been sent for.” Osseo obeyed the directions, and then took his seat in the lodge.

“Pity was shown to you,” resumed the king of the star, “on account of the contempt of your wife’s sister, who laughed at her ill-fortune, and ridiculed you while you were under the power of that wicked spirit, whom you overcame at the log. That spirit lives in the next lodge, being the small star you see on the left of mine, and be has always felt envious of my family, because we had greater power than he had, and especially on account of our having had the care committed to us of the female world.

He failed in several attempts to destroy your brothers-in-law and sisters-in-law, but succeeded at last in transforming yourself and your wife into decrepit old persons. You must be careful and not let the light of his beams fall on you, while you are here, for therein is the power of his enchantment; a, ray of light is the bow and arrows he uses.”

Osseo lived happy and contented in the parental lodge, and in due time his wife presented him with a son, who grew up rapidly and was the image of his father. He was very quick and ready in learning everything that was done in his grandfather’s dominions, but he wished also to learn the art of hunting, for he had heard that this was a favorite pursuit below.

To gratify him his father made him a bow and arrows, and he then let the birds out of the cage that he might practice in shooting. He soon became expert, and the very first day brought down a bird, hut when he went to pick it up, to his amazement, it was a beautiful young woman with the arrow sticking in her breast. It was one of his younger aunts. The moment her blood fell upon the surface of that pure and spotless planet the charm was dissolved.

The boy immediately found himself sinking, but was partly upheld by something like wings, till he passed through the lower clouds, and he then suddenly dropped upon a high, romantic island in a large lake. He was pleased, on looking up, to see all his aunts and uncles following him in the form of birds, and he soon discovered the silver lodge, with his father and mother, descending with its waving barks looking like so many insects’ gilded wings. It rested on the highest cliffs of the island, and here they fixed their residence.

They all assumed their natural shapes, but were diminished to the size of fairies, and as a mark of homage to the King of the Evening Star, they never failed, on every pleasant evening, during the summer season, to join hands, and dance upon the top of the rocks.

These rocks were quickly observed by people of the area to be covered, in the moonlight evenings, with a larger sort of Puk Wudj Ininnes, or little men, and were called Mish-in-e-mok-in-ok-ong, or Turtle Spirits, and the island is named from them to this day.

Glare upon me in the darkness,

I can feel his icy fingers

Clasping mine amid the darkness!

Hiawatha! Hiawatha!”

Michilimackinac, the term alluded to, is the original French orthography of Mish-in-e-mok-in-ok-ong, the local form (singular and plural) of Turtle Spirits.

Their shining lodge can be seen in the summer evenings when the moon shines strongly on the pinnacles of the rocks, and the fishermen, who go near those high cliffs at night, have even heard the voices of the happy little dancers.

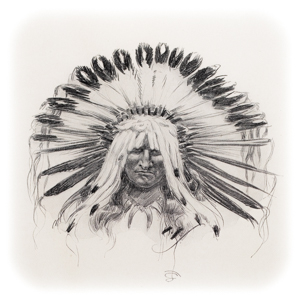

Pauguk. Pauguk is the personification of death. He is represented as existing without flesh or blood. He is a hunter, and besides his bow and arrows, is armed with a war club. But he hunts only men, women and children. He is an object of dread and horror. To see him is a sure indication of death.

Some accounts represent his bones as covered by a thin transparent skin, and his eye sockets as filled with balls of fire. He never speaks. His limbs never assume the rotundity of life, neither is he to be confused with the numerous class of minor Manitoes, or spirits.

He does not possess the power of metamorphosis. Unvaried in repulsiveness, he is ever an object of fear; and often has the warrior—flushed with the ardor of battle, rushing forward to seize the prize of victory—clasped the cold and bony hand of Pauguk.